Ashburton Art Gallery, New Zealand

9 December 20924 – 7 February 2025

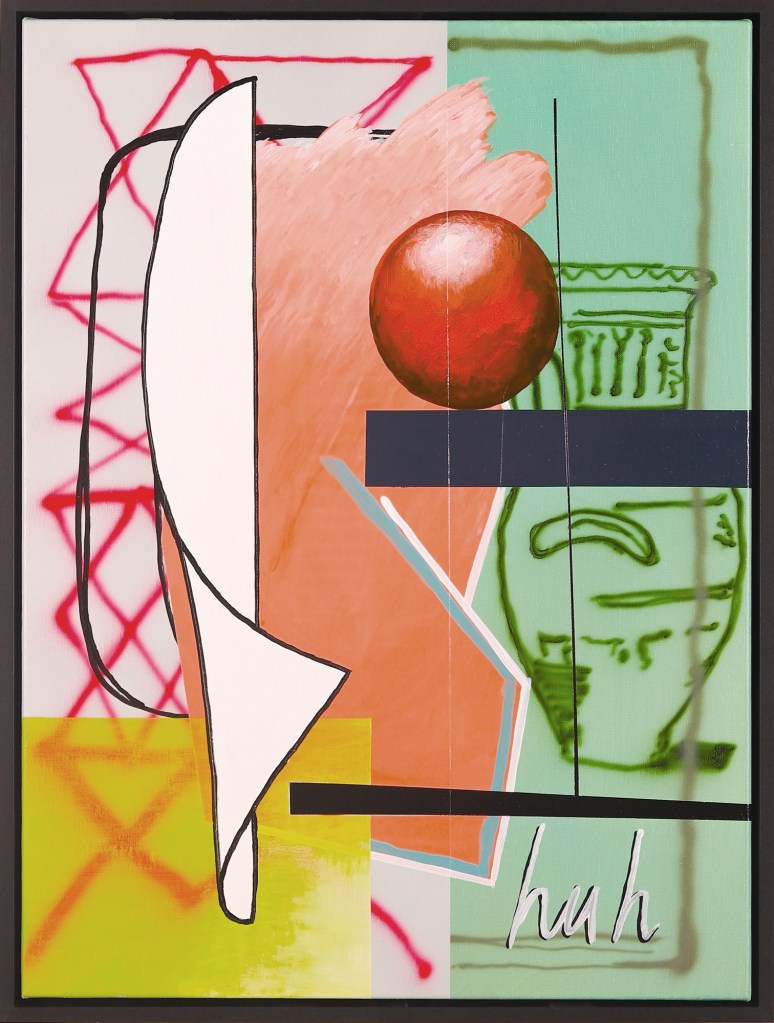

(Private Collection Dunedin)

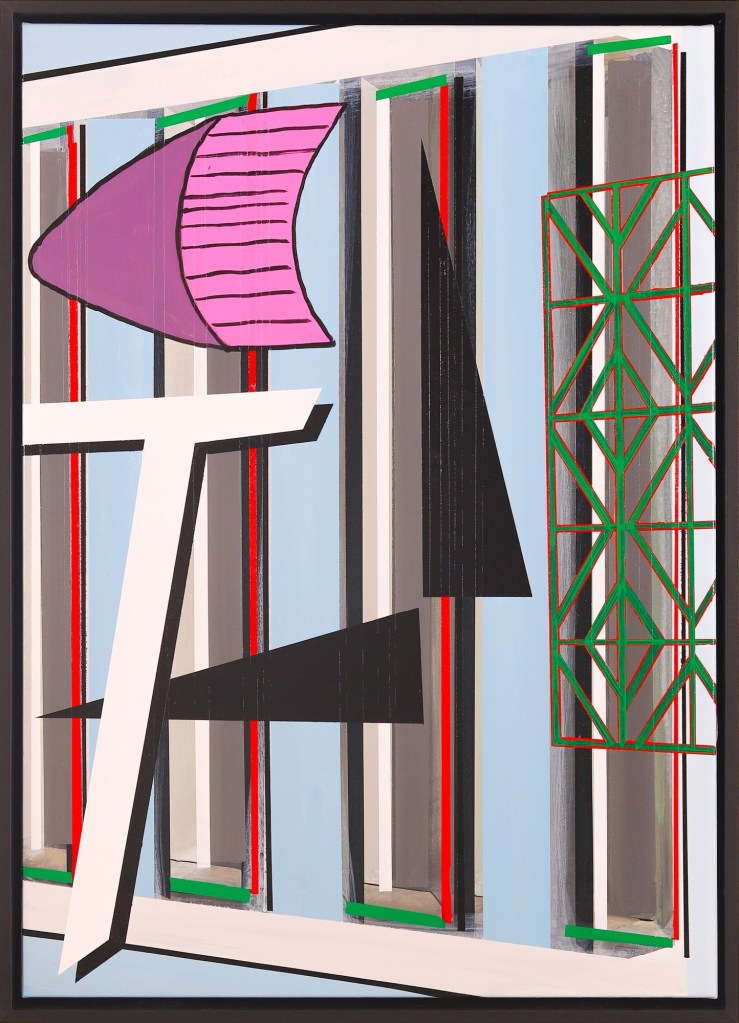

(Private collection Dunedin)

Michael Greaves – Falling if not Flying

The ancient Greek parable of Icarus contains at least two lessons for the painter. Daedalus, master sculptor and craftsman, was imprisoned with son Icarus in a high tower by King Minos of Crete. In order to escape, Daedalus studied the dynamics of birds in flight, and by collecting feathers and fastening them together with wax, fabricated two pairs of airworthy wings. Father and son leaped from the tower and flew to freedom. Before escaping, Daedalus cautioned: “Let me warn you, Icarus, to take the middle way, in case the moisture weighs down your wings if you fly too low, or if you go too high, the sun scorches them. Travel between the extremes.” Icarus, not taking heed of these instructions, sealed his fate. Overcome by the thrill of flight, he flew too close to the sun, which melted the wax and disintegrated the wings, plunging him into the sea.

Firstly, this parable could illustrate the folly of attempting to replicate precisely a thing of the world – the limitations of the wings’ materials meant they hadn’t the ability to soar as high as a real bird’s. To paint is to similarly attempt, but fail in replicating precisely an object, thought or idea in an image. Secondly, it allegorises the fine line that painting must negotiate in succeeding and failing on its own terms. The freedom that painting affords comes with the risk that the work will not succeed; of overstepping the boundaries and ‘flying too close to the sun’. Perhaps weeks and months of work is undone through excess ambition, the painting’s coherence brought down through striving towards a resolution that proves elusive.

Michael Greaves is an artist acutely aware of painting’s history and the burden it places on the contemporary painter. For today’s painter this requires faith that painting still has something to say in the twenty-first century; that it can transmit something beyond mere mimesis. For Greaves, painting as a ‘window to the world’ cannot rest on its laurels as the medium of reproduction, long usurped by photography, or for conveying a narrative – achieved more simply through film. It must provide something more.

To Greaves, painting is world making, and in this sense it shares affinities with the Internet. There is a world within the canvas and one within the screen: both can present three-dimensional illusions on two dimensional surfaces. Both are palimpsests, albeit one consists of a rapid replacement of imagery, where the pace of visual information is relentless, discontinuous, and at times overwhelming. This is in contrast to the slow building up of layers over a much longer time period in a painting, where the intention is for a slow observation of the nuances of composition, texture and tone, rather than hurried saccadic glances.

Greaves has described ‘painting the current historical situation’, and there is no greater recent event in collective history than the COVID-19 pandemic. Conditions of confinement, the experience of a world compressed, both spatially and temporally – these restrictions resulted in a myopic sense of the world’s boundaries and time was shaken loose from quotidian routines. In this period of simultaneous stasis and the accelerated pace and quantity of data, there was the inducement to paint responding to interiority – making material the concept, the memory and the idea. Because of the instability of memory, to attempt this is to chase shadows.

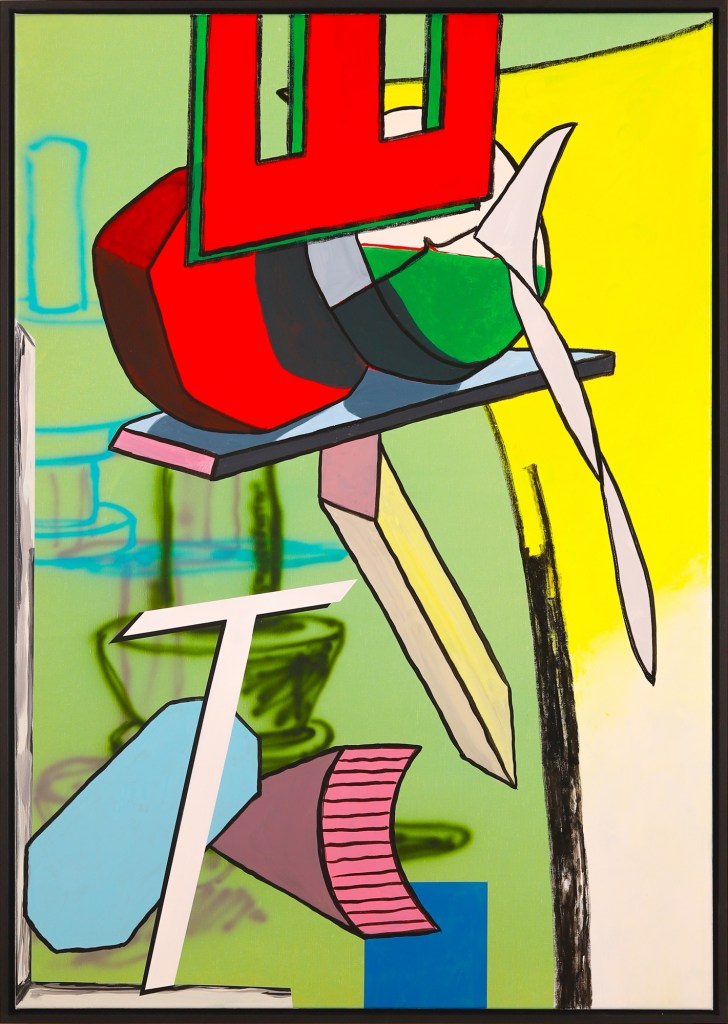

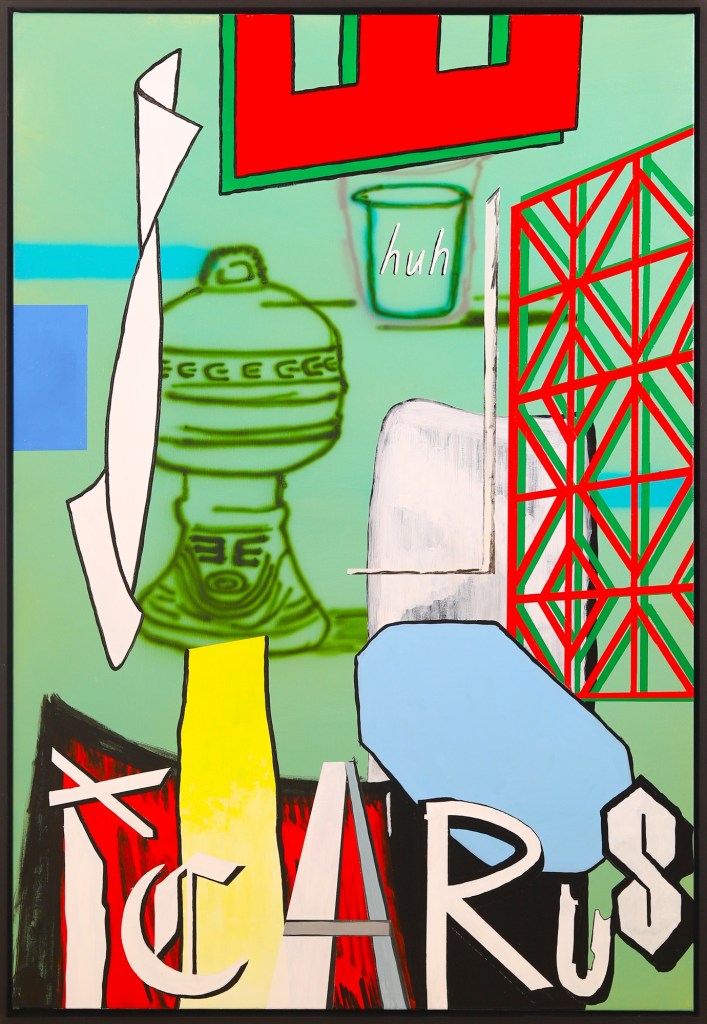

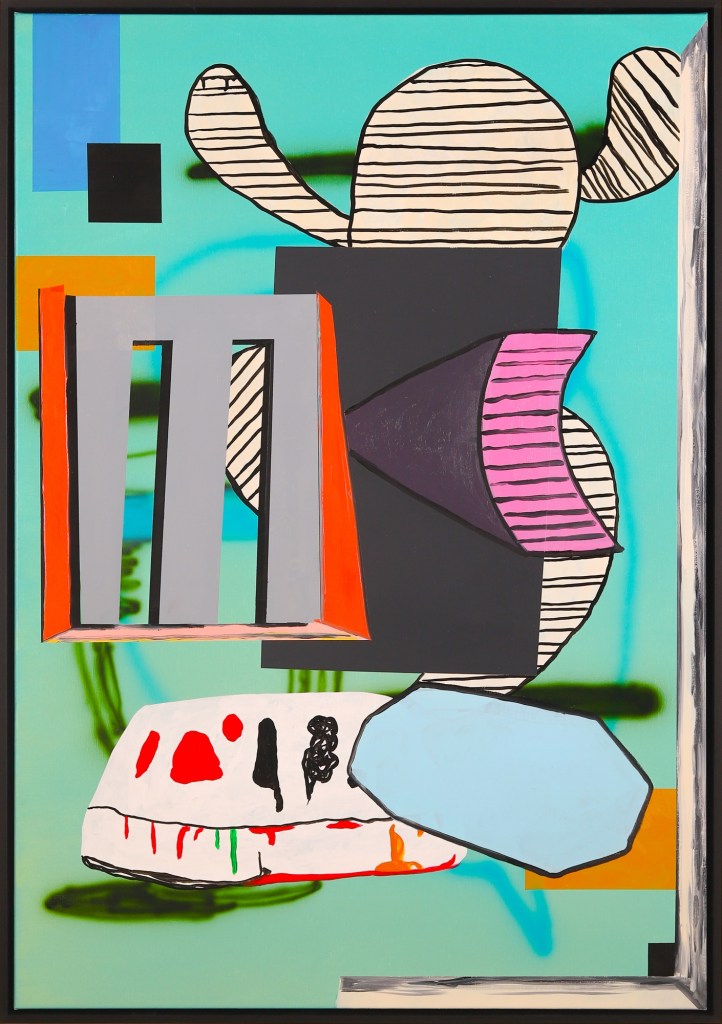

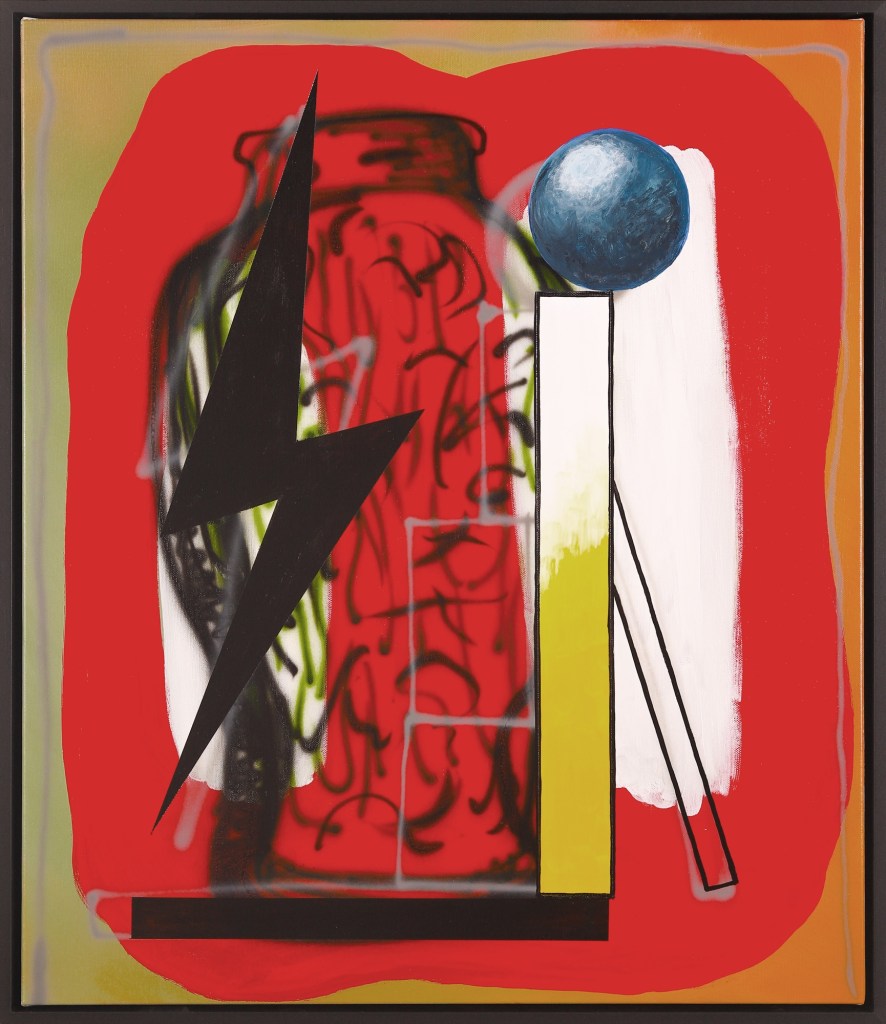

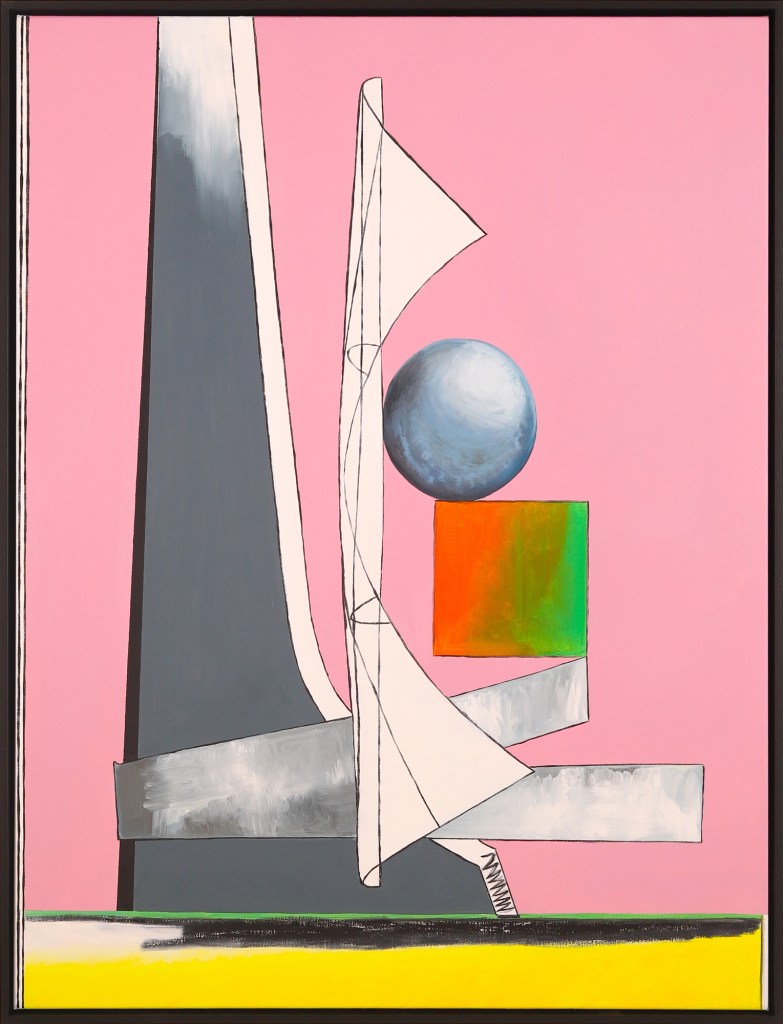

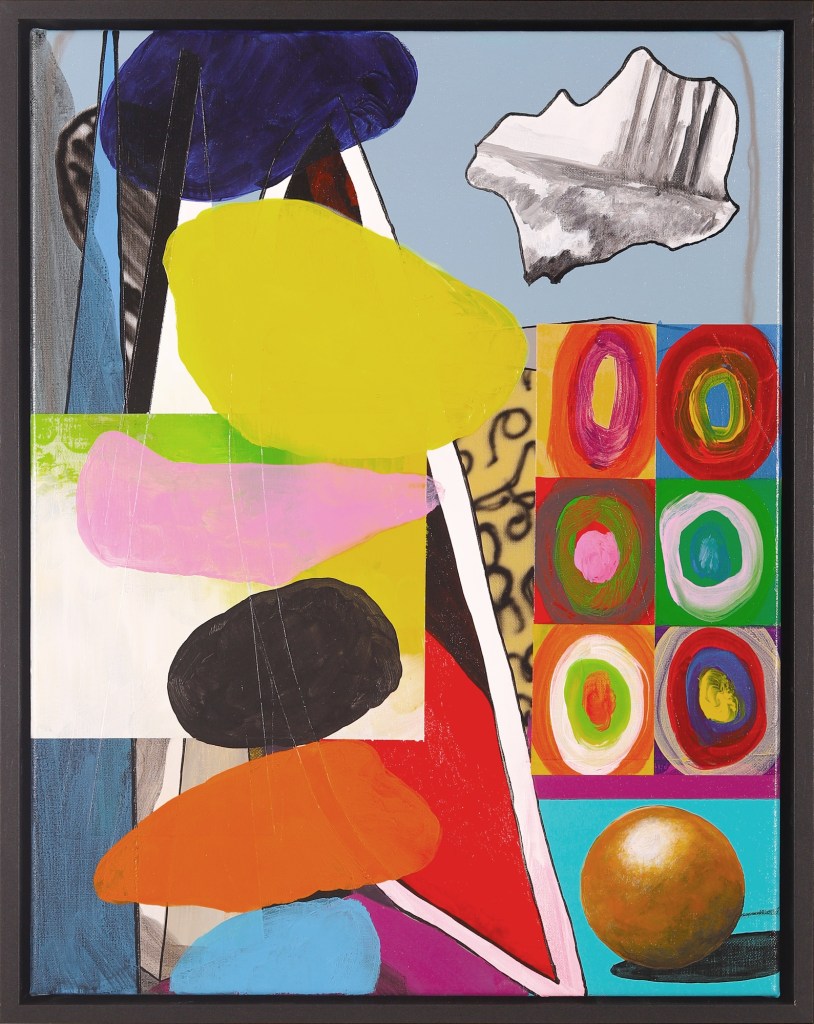

The paintings seem hermetically sealed, the objects within forming their own internal world, their own particular logic within an airless environment. However, as a suite of works, they unfold more like sentences in a paragraph. There are recurring ‘words’ within them – the articles, connectives, prepositions, and quantifiers that bind a sentence together and construct its meaning. These are the spheres, crosses, rods, lattices and the ambiguous shapes that sit frustratingly on the cusp of recognisable objecthood – a memory or déjà vu that evades apprehension. These duplicated symbols link each sentence together within the paragraph.

There are images of Greek amphora-like forms visible in some of the paintings’ earlier layers, and are partially obscured by overpainted imagery. They are rendered with an airbrush, so are distinctly contrasted to the rest of the objects. They are the unambiguous forms that link the paintings back to the Greek origins of the Icarus myth. In the work Icarus, the word is constructed from approximate shapes and appropriated letterforms, including the cryptic stylised ‘S’.

Aware of the impossibility of creating an image with direct fidelity to an idea, Greaves acknowledges the inevitable loss that occurs in this act of translation. This ‘failure’ however results in the creation of further possibilities for the rendering of objects, delineating a new set of parameters which were not available prior. This process he describes as a ‘clearing house’ for ideas, which allows new perceptions to open up. The viewer also becomes an ‘active agent’ in the painting process, bringing their own memories and associations in the act of viewing. Associating different components within pictorial space, the works create potential for moments of affect and realisation.

Perhaps the twisted shape, replicated in several works and resembling a curling napkin, torsioned by gravitational forces, could possibly stand in for the plunging Icarus, his world dissolving into mere colour and shape as he plummets. Suspended in pictorial space, the object becomes a body contending with its own fragile limitations, and by analogy the limitations of painting as human endeavour.

James Hope, Curator Ashburton Art Gallery. December 2024